The column below is written by Robert Reid. Robert has written a couple dozen guidebooks for Lonely Planet and reguraly appears to discuss travel trends on national television. You can follow him on Twitter (@ReidOnTravel) and his website by the same name. The text was originally published on the National Geographic website. The reason why I wanted to share it here is obvious: I agree with it. Robert writes about how much of the attention of travellers is drawn away from their experiences and to the technology surrounding is. From cameras to social media, they all distract us from seeing what we need to see and experiencing what we need to experience when travelling.

« THE SECRET TO REMEMBERING TRAVEL »

Whenever I look through all those files of things I’ve saved over the years, I usually stumble upon some long-forgotten newspaper article I tucked away. I give it a casual glance, turn it over, then invariably find that whatever’s on the back is more interesting. Serendipity seems to win out over planning every time.

Travel’s like that. No matter how many journals I fill, photos I take, tweets I send, I find that oftentimes I “document” the wrong things.

While living and teaching English in Vietnam in the late 90s, I filled my journal with reviews of the pirated VHS movies I devoured in between classes. Tragically, not one word described life in an alley off Phan Kế Bính Street in Ho Chi Minh City, a place in the throes of wild transition.

Similarly, while studying in Russia just after the fall of the USSR, I snapped roll after roll of onion-domed cathedrals that haven’t changed for centuries, ignoring the babushkas holding toothbrushes for sale outside Metro exits – a telling snapshot of the country’s first baby steps into capitalism, now long gone.

Not that there’s anything wrong with gold-topped churches, of course, but I ended up “capturing” the same Russia people can capture today. Now, when I go on trips, I try to listen to what Future Robert is trying to tell Present Robert to notice, to record, to remember.

This isn’t as easy as it sounds, but it’s worth bringing up since most of us tend to over-document when we travel these days. Armed with smartphones and virtually limitless memory cards, we take hundreds if not thousands of photos without a second thought. And unlike before, we actually share them – instantly – with our circles on Facebook or Twitter.

That’d be fine, but I frequently catch myself rushing like a Black Friday shopper to spread news of my travels in real time. Last week in eastern Oregon, I jumped out of the car at the Clarno Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, snapped a photo, touched it up with the most realistic of the unrealistic Instagram filters, and sent it off. This is all before I even bothered to take a non-virtual look at the fossilized land plants and animals in the 44-million-year-old volcanic mudflow.

The antidote to the nod-and-go approach (a la Clark Griswold at the Grand Canyon) is simple: just slow down.

This isn’t a unique observation, or even a new one. When photography was just getting off the ground in the Victorian era, English art critic John Ruskin tsk-tsked over how travelers ended up paying less attention when they had a camera in their hand. His answer was to supply basic advice on how to sketch, reasoning that taking the time to crank out even the most primitive of drawings can help anyone “see” a place better.

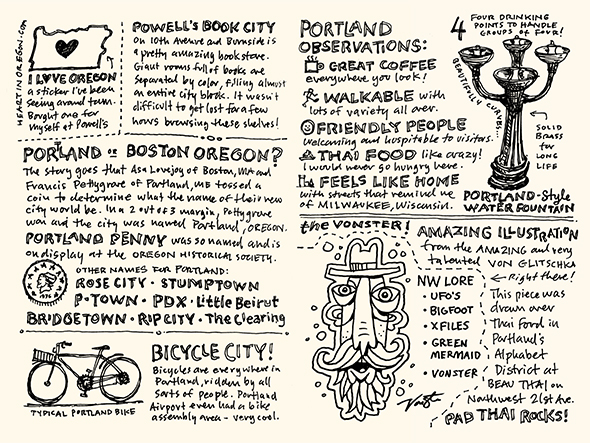

That mantra is certainly echoed by Wisconsin-based artist/author Mike Rohde, whose fun new book, The Sketchnote Handbook, illustrates how a few thoughtful drawings do a better job of capturing the spirit of an experience than pages upon pages of notes. Mike told me “sketching uses more of your brain’s capabilities…creating a more detailed, layered map,” and I agree with him.

The key to maximizing future memories, then, is to simply be present, to pay attention to the details that interest you, to look at them closely — perhaps even sketch them. What those details are only you know. (For Rohde, Portland, Oregon’s points of interest included a drinking fountain with four faucets (see above).)

Most people take photos when they travel, but not everyone jots down drawings and descriptions in a journal. In an essay in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Joan Didion claims only “anxious malcontents,” such as herself, bother to do so. Maybe more should.

I’ve filled 30-some notebooks with a decade’s worth of lost (as of yet, at least) travel moments. Lately I’ve been transcribing each of them, page by page. It’s been amazing. I enjoy the unfiltered tangents: scribbles about train times, sketches of a bus driver’s dramatic mustache, (bad) ideas for songs I’ll never write. But in the best and most illuminating moments, these musings can bring back forgotten memories and lend color to cherished ones.

I’ve been telling friends the story about a “goat whisperer” I encountered on a train in Bulgaria for years, but when I sat down to write about it a few months back, I was able to paint the picture more clearly because I had thought to record how the gray-haired man tapped his foot as he whispered, that the baby goat was wrapped snuggly in a blue-and-red striped plastic bag, and how it happened en route to Vidin on what would have been my dad’s 65th birthday.

I like to think that each trip has at least one “moment” like this – one that teaches us a lasting lesson or informs how we see the world. They can’t be planned, of course, but I try to be present enough to know when one might be happening so I don’t just slow down to enjoy it; I stop altogether.

Last October, I traveled to south-central France to follow in the footsteps Robert Louis Stevenson took in his autobiographical Travels in the Cévennes with a Donkey. When I came to a small lake between the villages of Cheylard and Luc, I knew I was near the spot where Stevenson had offered up what would become one of the book’s enduring quotations: “I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.”

And I disobeyed him. I stopped instead – to look and listen.

Only then did I hear a handful of dry leaves falling through the trees and birds stopping their songs then starting up again. Only then did I notice the spiky chestnut shells below my feet and how the birch trees resembled a bowl of Fruity Pebbles swaying in the wind — details Stevenson had noted, too (okay, except for the Fruity Pebbles part).

I didn’t photograph or Tweet any of that, but I sure do remember it.

Source of the picture and the text: NationalGraphic.com .

Average Rating